This is a long one, so I'm putting the summary at the top

Summary

Take daily measurements of your weight and waking temperature, at the same point in your daily cycle. Your natural wake-up point is probably best. Graph the results.

Say what you think is going to happen next. Write it down, preferably in public. That will force you to think, and help you to realise when you're wrong about something.

When trying to work out what's happening, you're probably best to look at the trend of the seven-day average rather than at the individual data points.

Try not to do anything to influence your measurements that doesn't affect what you're really trying to influence. You're trying to listen to what Nature is telling you, not to overwrite its faint signal with what you want to happen.

If you make a deliberate experimental change in what you eat, ignore the first few days' data when trying to work out what the intervention does. You'll have a better idea of what's going on once you change your diet back to normal, and transient water-weight changes reverse.

As far as possible, eat whenever you're hungry, and don't eat when you're not. Willpower in this respect is your enemy here, both for your epistemic and physical health.

What Do We Want

I'm mainly interested in fixing my broken metabolism. But I have far more readers than can be explained by the natural level of people who are fascinated by an old man going on about his health problems.

I think that what most people here are really interested in here is weight loss. And I am interested in that too!

And actually, no-one's really interested in weight loss per se. If you just want to lose weight, carry a load of helium balloons around, stop eating and drinking, take a load of arsenic, and blow your legs off near a good hospital. (This is medical advice. Don't take it...)

I think people are more interested in 'reducing the amount of body fat that I'm carrying around to the sort of level which humans are designed for'.

And I think that most people are actually secretly interested in looking hot, which by some bizarre and inexplicable coincidence is roughly the same thing as far as body fat levels are concerned.

Evidence from hot-looking primitive tribes (https://theheartattackdiet.substack.com/p/yes-you-have-a-homeostat) and Victorian whores (https://theheartattackdiet.substack.com/p/the-fat-whores-of-london ) learns us that that probably means a BMI of around 22, with a bit of variation based on how heavy-built you are.

For most of my life I was perfectly happy and good-looking at a BMI of 27. As an old man I should probably weigh a bit less than that now, because I don't have the muscles I used to have. If you're really skinny, 18 or so might be alright. At any rate, in the modern world, there's no good reason to carry around large fat reserves, so if you're healthy skinny, even less than that might be ok, although at that point you're starting to lose the hotness benefits.

If you want to work out what the other sex actually likes, look at or read porn aimed at the other sex, not magazines aimed at your own sex. And don't for the Love of God ask the other sex, or believe what you read, or listen to the wise, because almost everyone's lying for complex reasons.

I'm a bit old for all that now, but I do remember that it used to matter.

At any rate, let us all pretend that we're just innocently aiming for a BMI between 18 and 25, as is advised by the health authorities on the basis of that's what used to be normal. For once I think they’re right.

What We Can See

What we normally end up measuring is body weight. That is a most imperfect proxy for the fat levels that we're really interested in.

I've noticed several ways in which that can go wrong. As a very wise man once said, once a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.

So it's important to remove the things that make body weight measurements not the same thing as fat level measurements, if we're to see what is actually going on.

The Hours

First and most obvious is circadian rhythm. You're burning fuel of various sorts pretty much constantly all day, mainly to maintain your body temperature.

During your waking hours, you're eating food and drinking water, both of which cause your weight to rise. MIMO (mass in, mass out) is not quite a law of physics these days, but it's good enough for our purposes.

You mainly breathe out your weight!

When you burn a hydrocarbon fuel, either a fat or a sugar, you combine it with oxygen. All life is secret fire.

The hydrogen turns into water, and the carbon turns into carbon dioxide. By far the greater mass is the carbon dioxide, and that gets breathed out. Water can leave by several routes, some of which it seems indelicate to discuss on a respectable substack.

But mainly you are breathing in a certain mass of oxygen, and breathing out a greater mass of carbon dioxide and water.

Overnight your weight drops smoothly, during the day it mainly rises. A night’s sleep usually takes around 1kg off my weight.

We can get rid of this variation easily enough by making the weight measurements at the same point in the cycle every day. My own technique is to take a weight measurement almost immediately I get up, just after performing my morning ablutions, which often involve discarding slightly more water than I draw from the tap.

If you're thirsty when you get up, drink some water until you're not thirsty any more. Before you take your weight measurement.

Why? Because if you don't drink water when you're thirsty, you're likely to do that more when you think your weight should be going down, and less when you don't care too much. That's an obvious way of getting your experiments to tell you what you want to hear, rather than what is actually happening.

The skill is not to fool yourself, and you are very easy to fool.

I'd go further than that. If you find a way of fiddling your own measurements, like repeatedly trying your scale in different places on the floor, then you should deliberately do the opposite. Things like moving the scale around or staying thirsty for your morning measurement can't possibly affect your fat levels, so don't do them, because you'll bias your own measurements. If, every time you're tempted, you do the opposite thing, you'll eventually teach yourself not to fiddle your own data.

This is my Rule V, "No Goodharting". It's much more generally applicable than just when you're worrying about your weight. It is, for instance, one of the reasons that communism doesn't work. But that's a subject for a different substack.

(Coming soon on https://johnlawrenceaspden.substack.com/….)

The Days

Second and less obvious is weekly variation. Most of us live on a seven-day cycle, and if your Friday night involves a boatload of alcohol and your weekends involve eating with friends and family, there's likely a predictable cyclic difference between your weight on different days of the week even if there's nothing interesting going on with fat gain or loss.

This variation can be removed by taking a seven-day moving average. That will always include exactly one Friday, so it should remove the weekly-periodic effect.

Take your weight daily! That's a noise reduction measure in itself.

But keep your daily measurements, put them in a spreadsheet, and calculate that seven-day average and plot the trend line.

Try to mostly pay attention to the changes in the seven-day average. Looking at the daily measurements and trying to interpret them is fun, and I do it all the time, and you can learn from that, but the seven-day average is where you'll find the interesting trends.

Starvation, Gluttony and Sloth

Thirdly is the difference that you can make to your weight by consciously over-riding your body's signals about when to eat.

This is what most people mean by dieting! To deliberately starve yourself in order to lose weight. Forcing your body to rely on the fat that it has carefully stored against famine in the absence of new food to burn for fuel.

But you can also do it the other way. If you eat when you're not hungry, as I often do for social reasons, then your body will store the extra energy as fat, and your weight will go up.

Both these effects are actual genuine fat-loss or fat-gain. But neither of these things, I think, is really making much difference to your long-term fat percentage.

I think that unless your metabolism is really broken, your body will have a particular fat level that it's aiming for.

If you artificially use willpower to reduce your fat level, then your body will respond by making you hungry. You can use more willpower to keep the level low, but it doesn't seem a productive thing to do.

You'd need to use enormous willpower on a continuous basis to make any real difference to your weight, and you'd probably be making yourself ill by trying to maintain your body in a state that it isn't happy with. Psychologically you'll spend all your time thinking about food, and your metabolism will crash as it tries to go into famine-survival mode.

I'm sure this is possible, but I have trouble imagining that it's ever a good thing to do, and I can imagine plenty of ways in which it might be a very bad idea.

If you over-eat for some reason, then you'll gain weight, but your body will react to that by not feeling hungry. You'll actually find the thought of more food revolting. u/exfatloss calls this 'cement-truck satiety', but I think he's just describing what healthy people feel when their fat reserves are slightly higher than their body would like.

A feeling I’ve had all my life. A feeling as familiar as hunger.

It was big, surprising news to me that some people never feel that 'cement-truck satiety'. I think they must be very badly broken in some way.

But even if your metabolism is only slightly broken, the fat level that it's aiming for may not be a good level. You may be upsettingly overweight or painfully, even dangerously thin if you let your hunger signals determine when and what you eat.

But that's the problem you're trying to fix. The whole mystery. Why is your metabolism dysregulated? How can it be put back in order?

Changes in the fat level that your body wants to maintain are what we're trying to see here. The only thing that matters.

Essentially I think that weight loss or gain from ignoring your hunger and satiety signals is just another source of noise. You can avoid it by making sure that you always eat when you're hungry, and don't eat when you're not.

I actually think that's advice that's almost impossible to follow, but you can try to minimize the effect. If you're using willpower one way or the other, then you're probably well away from equilibrium, and probably doing yourself harm.

Water

After those three obvious sources, there are some more interesting and less obvious sources of weight-gain and loss.

The first is 'water-weight'. If you eat the same thing every day, then you should come into equilibrium, and the amount of water in your body should stay roughly the same.

But when you change what you eat, the amount of water that you're carrying can change.

Most obvious is water bound to glycogen. If you're eating normally, you'll have a considerable reserve of glycogen to use as immediate short-term fuel. That's bound to water, and as you use the glycogen, you don't need so much water, so you'll get rid of it one way or another. Glycogen is mainly made from carbohydrates.

If you suddenly change to a carbohydrate-free diet, then all that glycogen gets used up over a few days, and you can't replace it except by turning protein into glycogen. That's why no athlete in his right mind would do a keto diet and expect his athletic performance to be unchanged.

For me, that effect seems to involve losing around 1.5-2kg over the first week of a keto diet, on top of the fat loss that I'm really interested in. I think that's a normal experience for most people who try it.

That weight-loss is real, you can see it in your gut becoming less rounded, your trousers becoming looser, your muscles becoming more defined. You can see it in your face!

But it's also illusionary, in the sense that it's not at all what you actually care about. The minute you start eating carbohydrates again, you'll refill your glycogen stores, and you'll need all that water back, and you'll get heavier again.

Often if the diet is really causing fat loss, you'll see the two effects together, and lose a truly dramatic amount of weight in the first week. Part of that is water-weight, which doesn't matter, and part of it is genuine fat loss.

But there are other reasons to store and discard water. If you change the amount of salt you're eating, that can cause you to lose or gain water. And presumably all sorts of other electrolytes and other chemicals in your food and drink can affect the amount of water you're carrying.

So there's always a run-in period if you change what you're eating, and you have to take the first few days of any new diet cum grano salis.

After a few days, your water stores should have adjusted, and the trend after that is likely to be real fat loss or gain.

You'll only actually find out what's really happened when you go back to eating normally and your water levels go back to normal.

You might find that most of what you thought of as weight loss just goes away immediately. In which case your diet didn't do anything interesting, it was all just water-weight.

You might even find that water-weight gain has masked real fat loss, and that you were getting heavier while losing fat.

The Stochastic Dustbin

Finally there just seems to be unavoidable day-to-day variation in weight measurements. I've occasionally seen my weight change by two whole kilograms from day to day, without being able to see an obvious cause for that. There will always be a cause, but it's not usually obvious, and so not predictable.

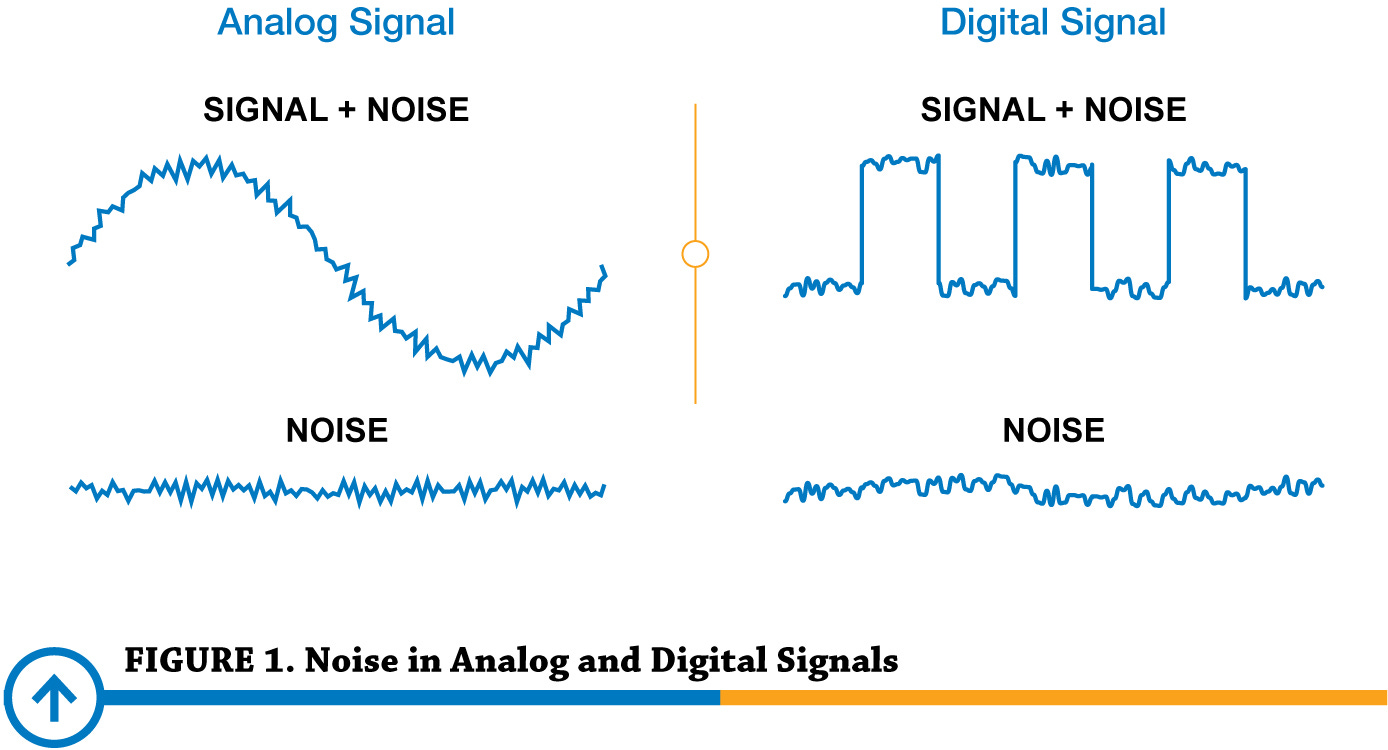

Things that aren't predictable are usually thought of as random, or 'stochastic', after the variation in where an arrow hits a target that isn't to do with anything the archer can control.

Luckily things that happen on their own often go away on their own. Looking at seven-day averages will eliminate a lot of that 'random' noise.

So:

Take daily measurements of your weight and waking temperature, at the same point in your daily cycle. Your natural wake-up point is probably best. Graph the results.

Say what you think is going to happen next. Write it down, preferably in public. That will force you to think, and help you to realise when you're wrong about something.

When trying to work out what's happening, you're probably best to look at the trend of the seven-day average rather than at the individual data points.

Try not to do anything to influence your measurements that doesn't affect what you're really trying to influence. You're trying to listen to what Nature is telling you, not to overwrite its faint signal with what you want to happen.

If you make a deliberate experimental change in what you eat, ignore the first few days' data when trying to work out what the intervention does. You'll have a better idea of what's going on once you change your diet back to normal, and transient water-weight changes reverse.

As far as possible, eat whenever you're hungry, and don't eat when you're not. Willpower in this respect is your enemy here, both for your epistemic and physical health.